I don’t want to read out of duty. There are hundreds of books in the history of the world that I love to death. I’m trying to stay awake and not bored and not rote. I’m trying to save my life.

I’m not interested in preserving the repertory. I’m interested in a continuum of intellect. If you have a problem with that distinction: Freud made up stories; go kill him.

Can social networking, blogging generate good books? In very rare occasions, yes. Justin Halpern (Shit My Dad Says) says that he was collecting notes for a screenplay, then the notes became blog posts, the posts became tweets, the tweets became a web site, book, TV show, etc. In the book each entry is 140 characters or fewer—the length of a tweet—and all of the subsections and mini-chapters are extremely short; the book is essentially a tape recording of the best lines of the author’s father, Sam, overdubbed with relatively brief monologues by the son. It’s not great or even good, probably, really, finally, but above all it’s not boring. Which is everything to me. Compare it to, say, Jonathan Franzen. (Franzen is, for me, the captain of the unfulfilled donnée. In The Corrections, he pretends to explore what is in fact a fascinating idea—that people, families, societies, and markets have a tendency to overcorrect—but he gives the merest lip service to unpacking this trope and settles instead for a painfully old-fashioned family album. Freedom: different metaphor; same result.) A huge number of novels are to me unconscionably boring. They don’t have an idea in their head, and if they do, they do absolutely nothing with that idea. Perhaps this is why Philip Roth, asked why he’s given up reading fiction in favor of history and biography, said, “I don’t know. I wised up.”

Books, if they want to survive, need to figure out how to coexist with contemporary culture and catalyze the same energies for literary purposes. That cut-to-the-bone, cut-to-the-chase quality: this is how to write and read now.

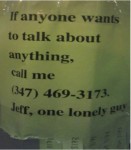

The undergraduates I teach are much more open to a new reading experience when it’s a blog. I know there have to be a hundred complex reasons why that is, but none of them changes the fact that un- or even anti-literary types haven’t stopped reading; they just don’t get as excited about the book form. The blog form: immediacy, relative lack of scrim between writer and reader, promised delivery of unmediated reality, pseudoartlessness, nakedness, comedy, real feeling hidden ten fathoms deep.

Another example: fifteen years ago, David Lipsky spent a couple of weeks with David Foster Wallace, then fourteen years later Lipsky went back and resurrected the notes. The resultant book, Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, pretends to be just a compilation of notes, and maybe that’s all it is, but to me it’s a debate between two sensibilities: desperate art and pure commerce. Lipsky, I hope, knows what he’s doing: evoking himself as the very quintessence of everything Wallace despised.

The book as such isn’t obsolete; inherently, it’s less immediate and raw, going as it does through the old-fashioned labyrinth of the publishing industry, and even when the book is printed and ready to go, you have either to get it at a store or to have it shipped to you via Amazon. For now, this is a constraint we can work around. I take it as a challenge: to give a book a “live,” up-to-date, aware, instant quality. There will always be a place for, say, the traditional novel that people read on the beach or chapter by chapter at bedtime for a month as a means of entertainment and escape. There is, though, this other, new form of reading that most books being published today don’t have an answer for. Even achieving a happy medium between the new and old reading experience is a great breakthrough.

Efficiency in the natural world: the brutal cunning of natural selection as it sculpts DNA within living organisms; DNA always pushing toward the most efficient journey to reproduction; water finding the briefest, easiest path downhill. Concision is crucial to contemporary art: boiling down to bare elements, reducing to basic notes (in both senses of the word). The paragraph-by-paragraph energy is everything.

.

Wait, there’s more! Read David Shields’ full piece, on the dubious distinction between nonfiction and fiction, the new literature of fact, and more, in the print issue of Little Star—or, for the frugal or connected—an economical downloadable PDF.