From the very beginning I found it difficult, debilitating and painful, to work for other people, with other people. As the years went by I found it increasingly difficult to work in the vicinity of other people, until that too became impossible. People recognized that I didn’t have a crowd, and they resented me for it. They found me disturbing, because I didn’t have that restraint on me. They recognized that I didn’t have people around ready to put a hand on my shoulder at the last minute, whispering in my ear, urging me to think it over. Though they themselves don’t think, are incapable of thinking, they sense the danger of someone whose thoughts are allowed to go on and on without check, they are made uneasy by the presence of someone who makes a habit of thinking matters all the way through to the end, to their logical rather than their emotional conclusion, who does not stop thinking at the point where he happens to feel comfortable, I have always believed. The thoughts, unchecked, either go round and round like a snake biting its tail or they shoot straight ahead like bullets, and one ends up a madman or an assassin, I think now.

The difficulty I have in being with people, the discomfort I feel in even a small crowd of people, stems from the fact that I can see into their souls, I sometimes think. At any rate I imagine I am seeing into their souls, and I suffer the consequences.

♦

The elation and immense relief that a released prisoner must feel when he steps form the prison door, while different in degree, are in kind like my feelings upon being released from boredom.

♦

Some things are becoming clear. It is becoming clear that I have to make a stand, for one. Or take a stand, or both. It is becoming clear that I must make a statement, for two. Lacking a statement, it is impossible to take (or make) a stand. Without a statement people have no idea what you are doing. Your statement is designed to clarify that, shed fresh light on it, situate it in relation to its origins, to what you hope to accomplish by it, and so forth. Without a statement your stand will appear arbitrary and stupid. On the other hand, statements minus stands are the sure marks of a blowhard. For me now to make a statement and then fail to take a stand is out of the question.

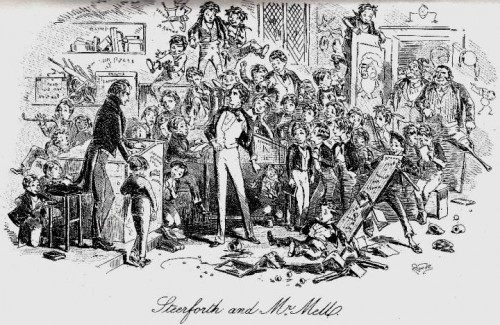

It was easy when all one had to do when making a statement was offend against good taste, when just making a statement provoked a stand. That was possible when there was still good taste, a code of aristocratic honor and after that a code of bourgeois correctness that could be violated. Now they are all louts from the outset. Especially the so-called educated classes, including the local middle class, are complete louts incapable of being offended. They cannot be offended even by good taste. At best they are puzzled, at worst they are amused.

♦

The few people I was still seeing showed by their expressions and by their avoidance behaviors that I had become a thoroughly tedious person, one who was also doggedly persistent and therefore completely annoying. As a thoroughly marginal person I was now forced by them, by that, into what was practically a clinical depression.

That was when Roy came and pulled me out of it.

I went from a socially excluded, potentially suicidal person to a marginal character with a dog.

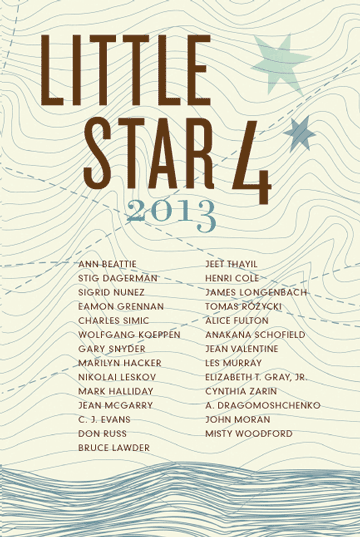

Read more in

Sam Savage was born in South Carolina in 1940. He was miseducated at Yale and the University of Heidelberg. For decades he wandered the great deserts of America and Europe. Lost from view, he discovered strange oases. In 2006, at the age of 65, he reappeared, leading a camel bearing manuscripts. The first of these manuscripts was Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife, which went on to become and international sensation, followed by The Cry of the Sloth and Glass. Savage resides in Madison, Wisconsin.

“If I’d had [this] novel three months earlier, I would have offered to make a special issue, or to run it as a serial… I think would’ve been just a coup.” Lorin Stein, in The Rumpus

We won’t tell you how this amazing book ends, but it is a beautiful (almost) surprise. A last quotation: “It is not even true that man is born, suffers, and dies. Even that is too much of a story.”