Sometime before Christmas we were paid a visit by Vlasta Kratochvílová. This woman, my father told me beforehand, was the bravest person he knew. She had risked her life many times over—to deliver mail to Terezín, to acquire needed medicines, and even to procure weapons.

I was expecting a heroic-looking woman, but when she arrived I beheld a quite ordinary woman, dressed somewhat provincially and about as old as my mother. She had brought with her some cakes she had baked and a Marbulínek picture book for my brother. To my surprise, she and my father kissed at the door, and then we sat at the table drinking real coffee (sent by my aunt in Canada) and munched on the homemade cakes. Mrs. Kratochvílová reminisced about the various people she had met and sometimes asked what had happened to them, but she always received the same reply: They were no longer alive; they didn’t come back.

Then she began to confide to Father her concern about what was happening. They were needlessly socializing everything, as if we hadn’t seen the chaos that ensued in Russia. She also didn’t understand why the Communists were behaving as if they alone had won the war. They were butting into everything and distributing false information about the resistance.

I could see Father didn’t like such talk,and if not for Mrs.Kratochvílová’s past he probably would have begun shouting at her, but instead he tried to explain that communism represented the future of humanity. The war had proved this. It was, after all, the Red Army that finally defeated Germany and chased the Germans out of our country. Only the larger factories, banks, and mines were supposed to be nationalized, and that was proper and just. Why should people be left to the mercies of some coal barons and the like who cared only about increasing their own profits? For them, the worker was merely a means. We needed a society that would ensure that nobody suffered, that people were able to live their lives with dignity. “I know what unemployment is. I worked at the Kolbenka factory and knew a lot of the workers. Most of them were masters of their craft, but they were let go anyway. What happened to them then? They went begging? Vlastička,” he addressed her almost tenderly, “I do not hide the fact that I am a Communist, and I’m proud of it.”

“But, Doctor,” she said in disbelief, “you can’t be serious.”

Read more in Little Star Weekly

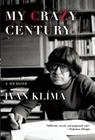

Long admired for his witty and intimate portraits of Czech life, in his new memoir My Crazy Century novelist Ivan Klima describes for the first time the internment in the Theresienstadt concentration camp that consumed four years of his childhood and his embrace and rejection of Communism in its aftermath, joining the distinguished band of Czech writers and thinkers—Havel, Skvorecky, Gruša, Seifert, Weil, Kundera—to counter Soviet oppression through art, eventually leading to the Charter 77 movement, the Velvet Revolution, and the Havel presidency.

Writes Philip Roth:

“In My Crazy Century the renowned Czech writer Ivan Klíma masterfully recounts, first, what it was like for him as a Jewish child confronting with his family the inhumanities of the Theresienstadt concentration camp situated at the edge of their hometown, Prague. Then, more fully, he painstakingly recalls what it was like for him and his countrymen after the Nazis thugs were driven out by the Soviet Army and replaced for four decades by the Communist thugs.

“How Klíma and his Czechoslovakian colleagues—among them some of the best writers in postwar Europe—endured the relentless infraction of their fundamental rights is chronicled here through the private history of one who steadily stood up to his oppressors and who has thought deeply about the degradation and deformation conferred on a decent society by the lawless thuggery of Europe’s 20th century ideological monsters, one who preached racial purity and the annihilation of the Jews, the other working-class purity and the annihilation of the wealthy, the bourgeoisie, and anyone capable of independent thought.

“In its telling, forthright intimacy Klima’s book merits a place alongside such eyewitness accounts of the evils of totalitarianism as Eugenia Ginzburg’s Within the Whirlwind and Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.”

Ivan Klima was born in Prague in 1931, in the middle of the Great Depression, to a middle-class Jewish family. During the Second World War, he spent three-and-a-half years in concentration camps. In the 1960s, he was the deputy editor-in-chief of Writer’s Union Weekly, and in 1967, he gave an important speech against censorship at the Writer’s Congress, was expelled from the Communist party and joined Czechoslovakia’s opposition movement. Following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Klíma’s books were blacklisted in his home country, but they were translated into several languages and published in 29 countries around the world. After the Velvet Revolution of 1989, Klíma’s books were rushed into print in Prague and sold hundreds of thousands of copies as people lined up to buy them for the first time in his native language. In 1990, Klíma was elected president of The Czech Republic’s PEN Club. He has written over twenty novels and books of essays, in addition to several plays. His best known books include My Merry Mornings (1985), Love and Garbage (1986), Judge on Trial (1991), My Golden Trades (1992), Waiting for the Dark, Waiting for the Light (1994), and No Saints or Angels (2001).

Craig Cravens is a Senior Lecturer in Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Texas at Austin.

From My Crazy Century, forthcoming from Grove Press. Copyright © 2009 by Ivan Klima; English translation copyright © 2013 by Craig Cravens; reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

Author appearances in New York City, Washington (in conversation with Paul Elie), Cambridge, and Philadelphia follow

Continue reading »