Little Star continues its serendipitous series of collages by important writers (see Mark Strand, here), with a sample from a new exhibition by Janet Malcolm, showing at Lori Bookstein Fine Art from January 9 to February 8, 2014. Malcolm’s “Abyss” appears as the cover image of Little Star Weekly this week.

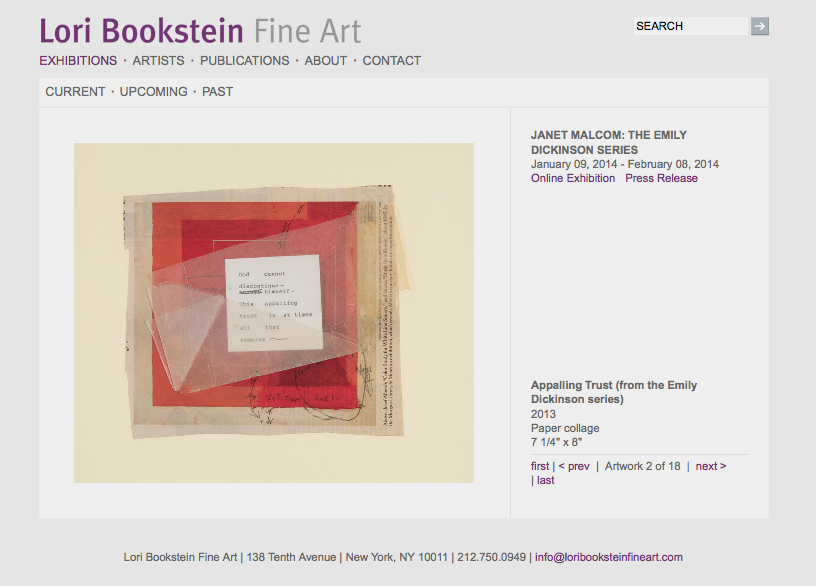

Her new project, her fifth exhibition of collages, is based on the late writings of Emily Dickinson, as discovered in Marta Werner’s book Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios: Scenes of Reading, Surfaces of Writing. A correspondence between Malcolm and Werner that will appear in Granta 126 recounts that the series itself records a sequence of serendipitous encounters, first Malcolm’s with Werner—she discovered the book in the library of a friend and was drawn to using it in her collage work, but was unable to find a copy until she wrote to Werner herself, who happily surrendered her last one to be cut and pasted. In Open Folios Werner herself juxtaposed facsimiles of Dickinson’s handwritten texts with her own typewritten transcripts, made on a variety of antique typewriters in the possession of her family. It was the typewritten texts that drew Malcolm, not the facsimiles: she saw in them “words that were wild and strange, and typing that evoked the world of the early twentieth-century avant-garde.”

Malcolm’s “Emily Dickinson Series” also includes a number of astronomical images, photographs, and charts of data. These we learn were drawn from a book called The Transit of Venus, 1631 to the Present, by Nick Lomb. Malcolm describes it as “an illustrated study of the rare astronomical event (it occurs in pairs eight years apart every hundred years) when the planet Venus crosses the disc of the sun and appears on its surface as a black circular dot [that] yielded a pair of spectacular black and white photographs of the sun made during the transit of 1874.” She continues, “I bought extra copies of the book so I could make more than two collages in which these large, mysterious orbs would figure. I also cut out a photograph of a bearded, depressed-looking man named David Peck Todd,” who became “a kind of stand-in” for Dickinson’s paramour, Judge Otis Lord. Malcolm later discovered that Todd was in fact the husband of Dickinson’s friend and eventual promoter, Mabel Loomis Todd, who herself had a long affair with Dickinson’s brother.

So the materials’ very randomness reveals hidden correspondences and affinities. One is struck by the correspondence too with Malcolm’s written work. A collage offers a group of objects that represent themselves as truthful in the most natural sense, they are what they are. Malcolm’s writings, with their delicate and rigorous attention to the observed world, assert a similar candor, and yet both bodies of evidence are immediately transformed by the maker’s shaping hand into something new: a created thing. The gap between the real, whatever that might be, and the representation is where the work sings.

Dickinson’s writings, at once direct and gestural, seem a perfect counterpoint to such an enterprise.

Janet Malcolm is the author of twelve books, most recently Forty-one False Starts: Essays on Artists and Writers, and a frequent contributor to The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books. Her series of photographs of burdock leaves appeared in a volume entitled Burdock, from Yale University Press.