Father lights a cigarette. I sit at my desk. Pour some seeds from the tube out in front of me. I open the English reader. He finishes drinking his coffee, gets off the bed, and throws a towel over his shoulder He lights a lamp and heads toward the bathroom to wash for prayer. When he comes back in, he stretches out the prayer rug on the floor. He prays the sundown prayer. He pulls open the glass doors to the balcony, and pushes out the wooden shutters to open them too. He drags the desk chair over to the narrow balcony, sits down, and lays his right arm on its metal railing. I stand next to him.

The balcony across from us is closed and dark. The window next to it is opened and lit up. We know it is a guest room that is only opened when they have visitors. Its curtains are rippling. There is a pale light in the apartment on the second floor where the iron merchant lives with his two wives. The light is in the first wife’s room. It’s put out and then comes on in the room of the second wife. The voice of Um Safwat screams at her son. Our Coptic neighbor Abu Wadie appears coming out from the entrance to the alley. He wears a dark suit. He carries sacks under his arms. He stops in front of the door to our house, and calls just like every night: “Wadie!” He exchanges good evenings with father. His wife answers him from the apartment above ours. Just like every night, he says to her: “The basket.” She lowers it down to him so he can put the sacks in it. The basket goes up slowly. He comes in to the house …

Read more in Little Star Weekly this week

Translated by Hosam Aboul-Ela

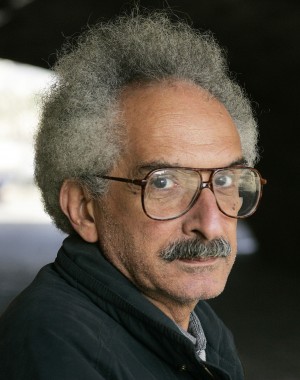

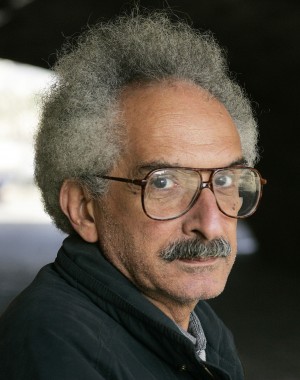

Sonallah Ibrahim amazed us last year with That Smell, a novel about a man recently released from an Egyptian prison in the 1960s, brilliantly translated and with a comprehensive introduction by Robyn Creswell. From Creswell we learned the epic arc of Ibrahim’s career: how within the familiar story of modern Egypt lay another story of its progressive intellectuals, defining modernism by reading Hemingway, Camus, and Woolf, sometimes from fragmentary newspaper accounts smuggled into prison, against the backdrop of their traditional culture and overwhelming political institutions. Published in 1966, That Smell was a breakthrough in Egyptian prose, delimiting an existential challenge within minutely detailed, affectless prose.

In this newer work from 2007, Ibrahim returns to an earlier Cairo but from another angle: a traditional family captured by poverty within the city’s eroding ancient ways. The deadpan style is used to equal but quite different effect: in That Smell, it registers a man’s struggle to recapture his connection with his world, piece by intimate piece; in Stealth, a young boy catalogues his surroundings in a bewildered effort to comprehend the emotionally stunted environment in which he finds himself, alone with a remote and lonely father. In Stealth, even more than That Smell, the method rewards us with a treasure-chest of its moment—how the lantern was lit, how the snack was bought in a paper cone, how the men gathered to talk in the evening, how the halvah was heated with milk for a humble dinner, a religious text’s instructions on household management. These artifacts are fascinating in themselves, but in the novel they ache with the boy’s need for the embrace of home.

Sonallah Ibrahim was born in 1937 in Cairo. He was drawn early to revolutionary politics, in part, Creswell recounts, by his childhood reading of adventure stories like Robin Hood and Captain Blood and their lesson of “sincerity, loyalty, self-sacrifice, aceticism, and chivalry.” He was arrested in 1959 when Nasser moved to repress Egypt’s leftists. It was his prison reading and its fragmentary exposure to literary modernism and the world’s arguments about changing literary language that forged his identity as a writer. He revolutionized Egyptian prose with That Smell, which was published a few years after his release in 1964. Eight novels novels later, he turned down a major Egyptian literary prize, condemning the Mubarek regime for its corruption and stifling of Egyptian thought and culture. His most recent novel is Ice (2011).

Hosam Aboul-Ela is an author and the translator of Soleiman Fayyad and Ibrahim Abdel Maguid.

Photo ©Philippe Matsas

Copyright ©2007 by Sonallah Ibrahim, translation copyright © 2009, 2014 by Hosam Aboul-Ela. From Stealth, published this month by New Directions